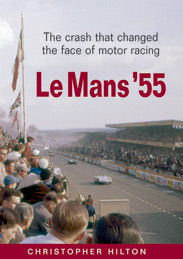

LeMans'55

by Christopher Hilton

Book

Review by Ed Potkai

At the 1955 Le Mans endurance race, a

Jaguar passed an Austin Healey then braked sharply for a

pit stop. The Healey swerved left into the path of a

faster Mercedes. The Mercedes collided with the Healey,

then launched into a spectator area, killing more than

80 people in addition to driver Pierre "Levegh".

This book is subtitled "The crash that changed the face

of motor Racing". It focuses entirely on the disaster,

its prelude, and its aftermath. The race winner is

mentioned only in relation to the consequences. Most

motorsports fans know of the incident but only vaguely.

This book makes the tragedy and the people involved very

real.

Whether the Titanic, Pearl Harbor, or

9/11, there is something about books which count down to

inevitable doom. They start slowly by describing

background. Then as fate approaches, we read faster,

all the time hoping that somehow it can be avoided.

Hilton leads us well. He's not afraid to use style to

keep us in the moment. He does not always use complete

sentences and can employ repetition for dramatic

effect.

After the crash has been described, the

pace of the book slows. No longer "exciting", it

becomes a lesson in good detective work. The author

analyzes the links in the "chain" of events and

circumstances that contributed to the disaster. The

work is well researched and documented. Hilton analyzes

the "facts", many of them conflicting, many biased, many

impossible. He respects that the witnesses did their

best to remember, but is not afraid to point out when

someone might have a reason to recall a prejudiced

version. And his clear bottom line is that no one truly

knows.

The author asks himself would he be able

to present his case to the three drivers if they were

standing alive before him. He concludes that he would.

And we too believe the evidence is presented as fairly

as humanly possible.

Was someone to blame or was it just a

"racing accident"? Having presented the evidence, the

author leaves the reader to draw his own judgement.

Although British himself, Hilton does not fault the

Frenchman or the Germans. He never makes a declarative

statement of blame. But the last sentence of chapter

eight leaves little doubt about his personal conclusion.

This book was written fifty years after

the incident. The author takes pains to remind us that

it was a much different time. Many of the actions taken

may seem callous. But virtually everyone at the track

that day had survived a terrible war only ten years

previous. British, French, or German, they had watched

their countries endure much destruction. They had all

seen days when 80 deaths was a tiny number. Death was

inevitable, especially in motor racing. Only three

months later, the Austin Healey driver crashed out of a

race in which three drivers burned to death.

Why would the author examine the accident

fifty years after the fact? The safety lessons have

long ago been implemented (however slowly). By

uncovering the facts and emotions, I think he wanted to

reach an understanding and to change a statistic into a

reality for us. And that is the reason we should read

it.

With such a sharp focus, this is not a

book for everyone. It presents dozens of names which

can be difficult to track. The graphics are adequate

but quite basic. Occasional sentences can be awkward to

read (look who's talking!). But this is a very fine

history which will fascinate many.

Postscript:

The driver who was waiting to relieve Levegh was

Connecticut's John Fitch. Within the year, Fitch

designed the Lime Rock Park race course. His top

priority was that no race car would ever invade a

spectator area. In more than fifty years at Lime Rock,

none has.

|